The Spiritual Hunt: Searching for Rimbaud’s Lost Manuscript

Editor’s note: The following piece was mailed to us by the publisher along with the manuscript of the English edition of “The Spiritual Hunt.” Consider it less a historical account than an initiation into the enduring myth of Arthur Rimbaud’s lost masterwork. Where truth ends and fiction begins is anyone’s guess.

I checked into the Hôtel Crystal just as dawn was breaking. The room was small and stained with time. From the window, I watched a bleary-eyed waiter drag crates of wine bottles into an alleyway and smash them one by one.

I made myself a stranger in Paris in order to find a book. A book that some consider lost. But I believe books are rarely lost. Rather, they wait. They bide their time as shards, fragments, phrases, and titles. A book has many lives, though some are more shattered than others.

The title I sought was “La Chasse spirituelle” (“The Spiritual Hunt”) by Arthur Rimbaud. For over a century, it survived only as a beguiling aside in a letter of Paul Verlaine’s, a fleeting reference to a new five-part manuscript by his gifted young paramour. Yet no such volume was ever bound, no edition pressed bearing this title in Rimbaud’s lifetime. The manuscript, left behind by Verlaine as he fled his family home due to numerous indiscretions, soon vanished and was presumed lost.

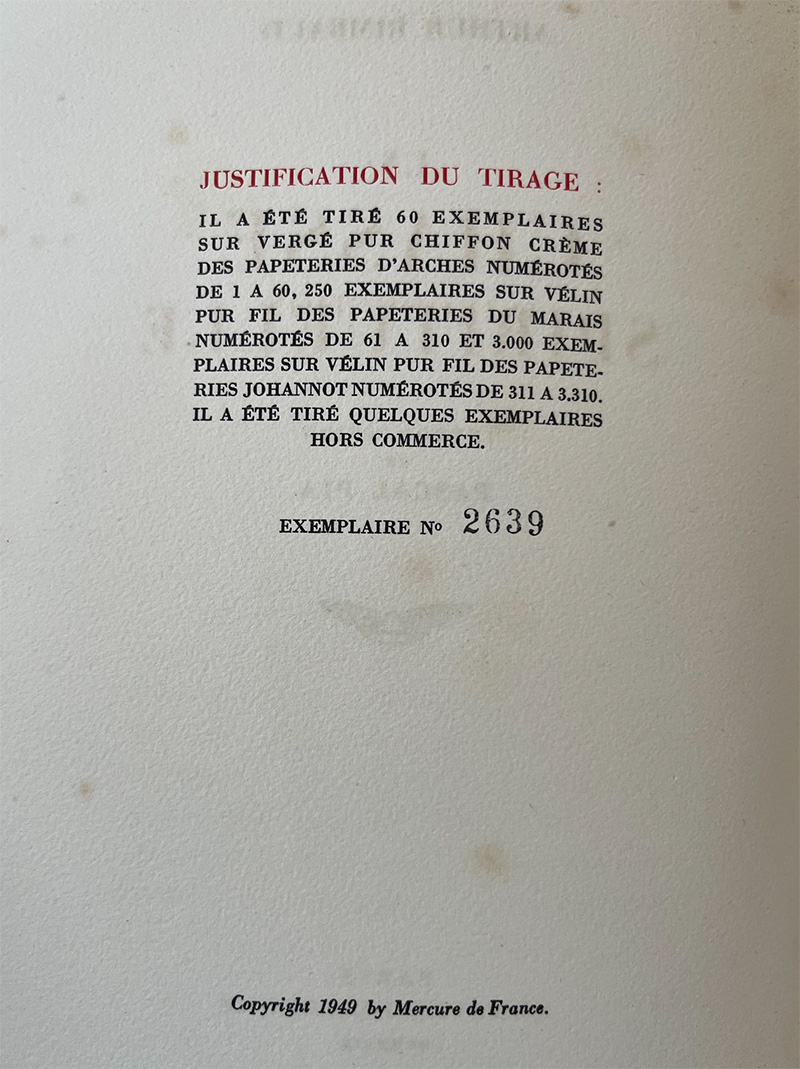

Whispers of an extant text of “The Spiritual Hunt” arose in the 1920s. Other once-lost poems of Rimbaud’s had resurfaced and were hailed as genuine. A reputable, if seedy, bookseller listed an unknown Rimbaud manuscript “in five parts” that was swiftly acquired. Less than a decade later a hand-written manuscript was supposedly in circulation amongst the literati, accompanied by proclamations of veracity. Still, no one seemed able to truly verify its origin and no publisher dared put their name behind it. That is, until May 1949, when editor Pascal Pia was somehow able to convince the storied Mercure de France of the authenticity of a manuscript and to print, at the risk of gross indignity, the first-ever typeset and bound edition of a book claiming to be Rimbaud’s “The Spiritual Hunt.”

To open this book is to peer through a keyhole into a roomful of mirrors. To see a face split across a thousand faces.

Mercure’s edition was an instant detonation igniting a civil war within France’s literary demimonde. Battle lines were drawn, trenches dug, and red ink spilled over its legitimacy. There were those partisans who dared believe and saw within this text the missing link in the glittering chain of Rimbaud’s poetic genius. In opposition, of course, there were those who immediately decried the work as a heinous fake and crass affront to the world of letters. But there were also those who, seizing upon the unprecedented critical and commercial furor, claimed that they were the authors of this text and stepped forward to accept their laurels.

There were radio interviews. Televised debates. Pamphlets pasted in the windows of bookshops and libraries. Endless press on this affaire Rimbaud which so sundered Paris. Yet ultimately it was a stalemate. Each side dug in with no clear consensus. No definitive proof was furnished, no revelation forthcoming, and the turmoil soon subsided. Mercure de France, beholden to the bottom line, hedged their bet and printed a new edition with a disclaimer regarding its authorship. They also ordered all remaining first editions of “The Spiritual Hunt” to be destroyed.

Whether the pulpers were on strike that week or just spectacularly casual about their work in that beautiful French fashion who can say, but it was only a day and a half before I came across a first edition of the Mercure in a bookshop by Boulevard Saint-Germain. The volume is exquisite in its design and production, an alchemical red-and-black layout printed on a fine-threaded vellum from the Johannot paper mill. I turned it over in my hands again and again, astounded to have found it, ensnared by the caduceus on the cover. I thanked the proprietor, who had retrieved it without a word from a flat file deep in the recesses of her ramshackle shop, and settled in at the Brasserie Lipp for an afternoon drink while perusing my controversial artifact.

It is apparent from the first page why these poems caused such an uproar. They are gemmed with visionary imagery and enchantments, a sort of barbarian stew that simmers in the nape of your neck. By the same token, they are distant and detached, entangled with an alien, sidereal vein. One can see the merits of an argument proposing it as a transitory piece in the oeuvre, an experiment. Its poetic force cannot be denied but I could also understand why one might hesitate before taking a leap of faith on its authorship. To open this book is to peer through a keyhole into a roomful of mirrors. To see a face split across a thousand faces. I thought of Rimbaud and how he once described himself: Je est un autre. I is an other.

I placed the book face down and stared off in distended reverie. Little seemed to cohere. Eventually, I tired of the Lipp’s stale beer and dull clatter and headed back to the Hôtel Crystal. Upon my entrance, the concierge waved me over and passed along a piece of mail that had arrived earlier in the day. There was no name on the envelope, only my room number. Inside was a small note letterpressed on fine cream linen cardstock:

To whom it may concern,

Your presence is requested at the Club Fortsas this evening at 9PM. Present this card to be granted entry.

Faithfully yours,

Evelina de Kiipt

Club Fortsas

145 Rue Lafayette

75010 Paris

It was 7:20pm. The Club was not too far from the Hôtel. Enough time for a few glasses of Ricard, which was how I measured time. I glanced at the entwined serpents on the Mercure edition cover. They stared back with divine indifference.

Three glasses later, I stepped out of the taxi to face the imposing Hausmann edifice of the Club Fortsas. Swirls and gnarls of limestone coalesced around a great blue door, ostensibly of wood but actually painted iron, above which stood a solid block inscribed with a single word: “Fidelis.”

The door, to my surprise, was open and led into a grand Beaux Arts foyer with Masonic tiling stretching down a narrow hall. At the end was a lectern where a young man in morning dress held court. I showed him the card and without a word he led me to a brass-gated elevator and set the lever to the fifth floor.

Evelina was waiting for me in the antechamber of the Club. It was drenched in oak and she wore all black. She told me that she was a friend of Mr. Carrington. I knew no one by that name but nodded nonetheless. She smiled and bade me entrance through the doors, which passing by I realized contained intricate carvings of an unknown alphabet.

The Club Fortsas was a stately place that had gone to seed. We hurried past the wooly furniture wrapped in yellow plastic and ducked beneath tottering mahogany shelves. I couldn’t tell how old Evelina was. She could’ve been 22 or she could’ve been a thousand. I followed her into a small parlor with a few vitrines in the center of the room. She motioned towards the vitrine closest to me. You may find this familiar, she said.

Beneath the glass lay a weathered sheet of vellum which unmistakably bore the handwriting of Arthur Rimbaud. I leaned in closer and was astounded. These paragraphs were poems from “The Spiritual Hunt.” I looked back at Evelina who stood with her arms crossed against the wall. The extract belonged to her father, purchased in Paris some 70 years ago. That’s all she knew. She excused herself and left me to fend with the foxed page.

I was foolish enough to have carried the Mercure edition in my coat. I hesitated before opening it, knowing the crossroads at which I stood. A pang of disquietude stirred in my stomach. The opening lines matched. But then a jolt of incredulity: the second verse did not. Neither the third. But then the endings did. Waves of incoherence subsumed me. I was at a reckoning and could reckon nothing. The book was found yet still lost.

Could the Mercure edition have originated from a different manuscript, a separate draft? Or maybe it came together piecemeal, the summation of scraps from archives and estates? Perhaps one of the so-called authors of the hoax, such as Nicholas Bataille, just so happened to write the exact words Rimbaud himself did. Of course, this vellum page in the Club Fortsas could very well itself be a fake. I was swirling in sources, caught knee-deep in myth. I left the parlor and Evelina was nowhere to be found. I made one last look at the manuscript and then took the elevator back down.

That was many years ago. Another lifetime, as they say. Since then “The Spiritual Hunt” has never left my mind nor my bedside, although answers prove more and more distant by the day. All involved in the affaire Rimbaud are long dead and my mail to the Club Fortsas is returned unopened.

So I am fortunate that a friend of mine, the translator and clairvoyant Emine Ersoy, shares a similar passion for these poems. Enclosed, you will find she has brilliantly rendered them in rapturous English, alongside facsimiles of the French originals. Now, over 75 years after their initial publication, “The Spiritual Hunt” returns to print. And thus I invite you, reader, to partake in this mystery of faith. But bear in mind the words of Enzio de Kiipt: myths have a nasty habit of being true enough.

Excerpted from “Pagan Holidays”

Translated by Emine Ersoy

I will bend the iron bars of an occidental sky and follow the steps of mages and scorned prophets, in anguish over our devoured relatives. But of no relation to obsolete beliefs, to the destiny of absurd and ruined virtues – free. The horror of indulgence precedes me. I will undo myself of elementary mannerisms. Cross my arms over the infinite. How simple it is! The superior barbarians had seen it all coming: liquidate wisdom and onward!

Soon, no more absence. Hearts will no longer be tortured. No more remedies. A force fed by silence, immobile. No more ancient will, no more backwards momentum. The implacable plain. The body still and vacant like a sanctuary. Turning one’s gaze to the inner shadow. Sleeping on the magic carpet and head full of terrifying realities – lighter than the dream of a well-behaved child – mysterious illusions, I will erase myself deliciously.

Nave restored with gold, streamless, stormless, I will soon approach the venerated port from which the sun ventures out to our commercial continents, our docks, our fruitful tides, our stopovers, our dreary beaches.

I want to walk on tightropes towards this primordial wisdom and marvelous world.

Mitch Anzuoni is the founder of Inpatient Press, which published “The Spiritual Hunt.” Seventy-five years after its initial imbroglio, the book is now available in English for the first time with a facsimile edition of the original.